どこでもならはくオンラインNNM ONLINE

LANGUAGE: 日本語 | ENGLISH | 中文 | 한국어

Buddhist Art Basics

Buddhist Art Basics

Buddhist Images and the Transmission of Buddhism

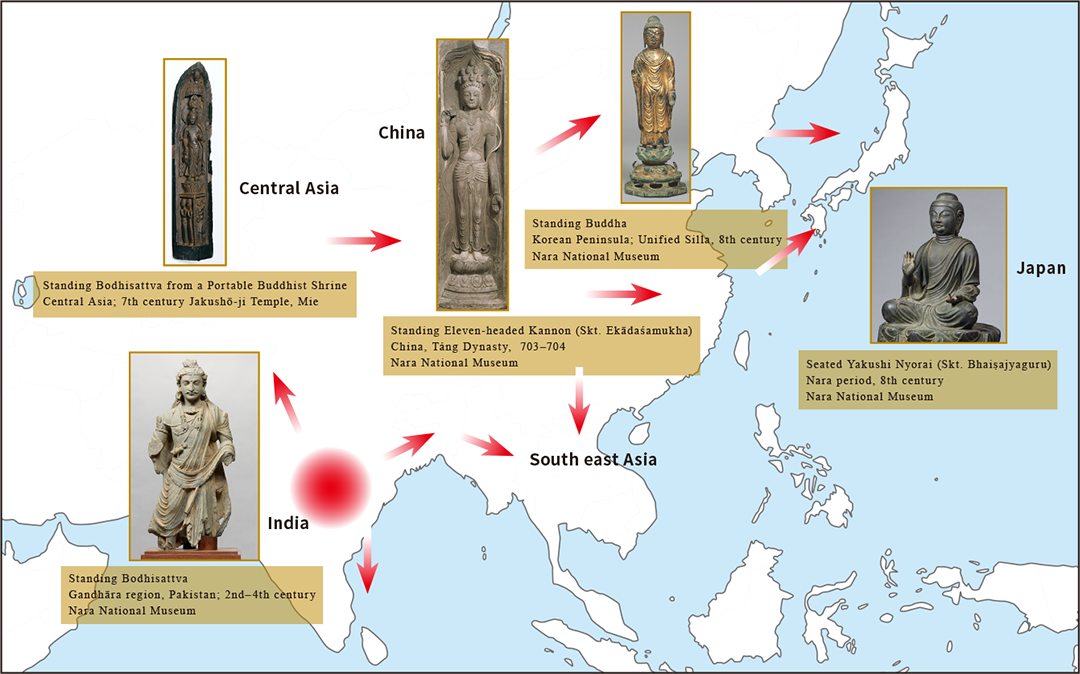

Śākyamuni—or Gautama Siddhārtha—was born as a prince in India around 2,500 years ago. The Buddhist tradition began with his lifetime; the worship of his material traces took hold among his followers when his bodily relics (Skt. śarīra) were enshrined in a stūpa after he had passed into parinirvāṇa. At first, these formless relics were the object of Buddhists’ reverence. Figural representations of Śākyamuni only appeared five or six centuries after his passing. The form of Śākyamuni was deified, adorned with marks distinguishing his body from those of ordinary human beings.

Next, there were developments of Buddhist doctrine that established Śākyamuni as but one of several Buddhas; the possibilities for Buddhist images and Buddhist iconography expanded with these teachings.

The myriad styles and forms that Buddhist images have assumed reflect the beliefs and religious aspirations of people living in various geographies and periods; Buddhism adapted to local beliefs and traditions in every region that it reached in its transmission across Asia.

Standing Bodhisattva

Gandhāra region, Pakistan; 2nd–4th century

Nara National Museum

Important Cultural Property

Standing Bodhisattva from a Portable Buddhist Shrine

Central Asia; 7th century

Jakushō-ji Temple, Mie

Important Cultural Property

Standing Eleven-headed Kannon (Skt. Ekādaśamukha)

China, Táng Dynasty, 703–704

Nara National Museum

Standing Buddha

Korean Peninsula; Unified Silla, 8th century

Nara National Museum

Important Cultural Property

Seated Yakushi Nyorai (Skt. Bhaiṣajyaguru)

Nara period, 8th century

Nara National Museum

Categories of Buddhist Statue

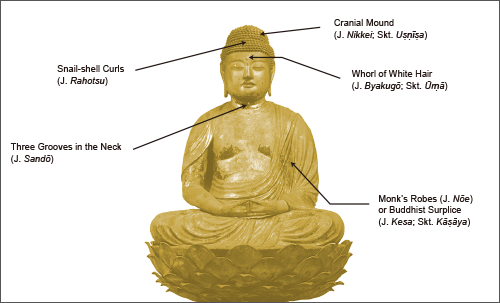

Nyorai (Skt. Tathāgata)

The term “Nyorai” refers to “a being who has reached enlightenment”—a Buddha. Their icons are modeled after those of the historical Buddha Śākyamuni. Icons of Buddhas have forms featuring a number of characteristics, or “marks,” that distinguish them from ordinary humans.

Seated Amida Nyorai (Skt. Amitābha)

Heian period, 12th century

Nara National Museum

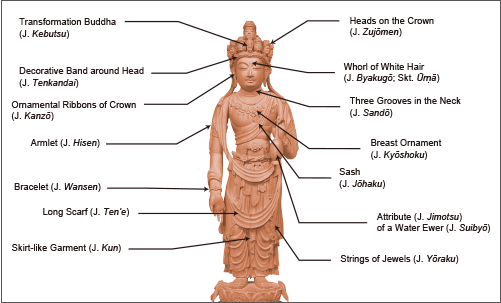

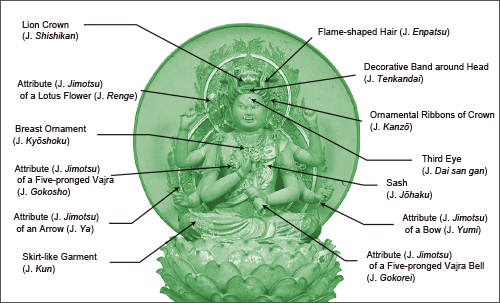

Bosatsu (Skt, Bodhisattva)

A bodhisattva, known in Japanese as “bosatsu,” is one advanced in their quest towards Buddhahood. Iconographically, they resemble Śākyamuni before he attained enlightenment. As Śākyamuni was the prince of a small country located in South Asia, bodhisattvas likewise arrive in the attire of Indian nobility. There are a great many bodhisattvas; all of them rescue sentient beings from various kinds of danger and suffering.

Important Cultural Property

Standing Eleven-Headed Kannon (Skt. Avalokiteśvara)

Nara to Heian period, 8th–9th century

Nara National Museum

Myōō (Skt. Vidya-rāja)

Myōō, or Wisdom Kings, are buddhas hailing from esoteric traditions of Buddhism (J. mikkyō). They are thought to be strong enough to conquer any foe or power, and they take on daunting forms to frighten those who have strayed from the teachings of the correct path. Myōō with multiple arms and faces reflect their mikkyō context.

Important Cultural Property

Seated Aizen Myōō (Skt. Rāga-rāja)

Kamakura period, 1256 (Kenchō 8)

Nara National Museum

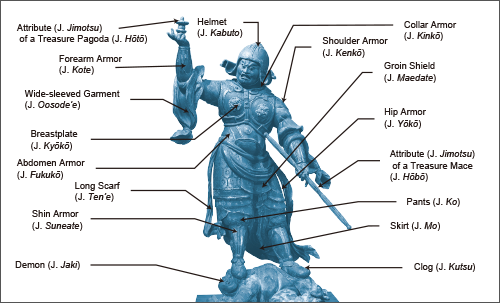

Heavenly Beings (J. Tenbu; Skt. Deva)

The class of deities known as the Heavenly Beings originated in ancient Indian religious traditions. They were enfolded into the Buddhist pantheon to serve as protectors of Buddhist teachings and followers. (The Heavenly Beings are believed to have converted to Buddhism, taking on this benevolent role in turn.) In East Asia, they often appear wearing the attire of Chinese nobility or military commanders. Goddesses and other female deities belong to this group as well.

Important Cultural Property

Standing Tamonten (Skt. Vaiśravaṇa)

Heian to Kamakura period, 11th–12th century

Nara National Museum

Kami (Shintō Deities)

In the distant past, local Japanese deities were not depicted physically. However, statues of Kami began to be created with Buddhism’s influence.

Seated Male and Female Deities

Heian period, 12th century

Nara National Museum

Portrait Sculpture

Figures of towering importance in the history of Buddhism had icon statues made in their likeness.

left : Standing Namubutsu Taishi (Prince Shōtoku)

Kamakura period, 13 –14th century

Nara National Museum

right : Important Cultural Property

Seated Chōgen Shōnin

Kamakura period, 1234 (Tenpuku 2)

Jōdo-ji Temple, Hyōgo

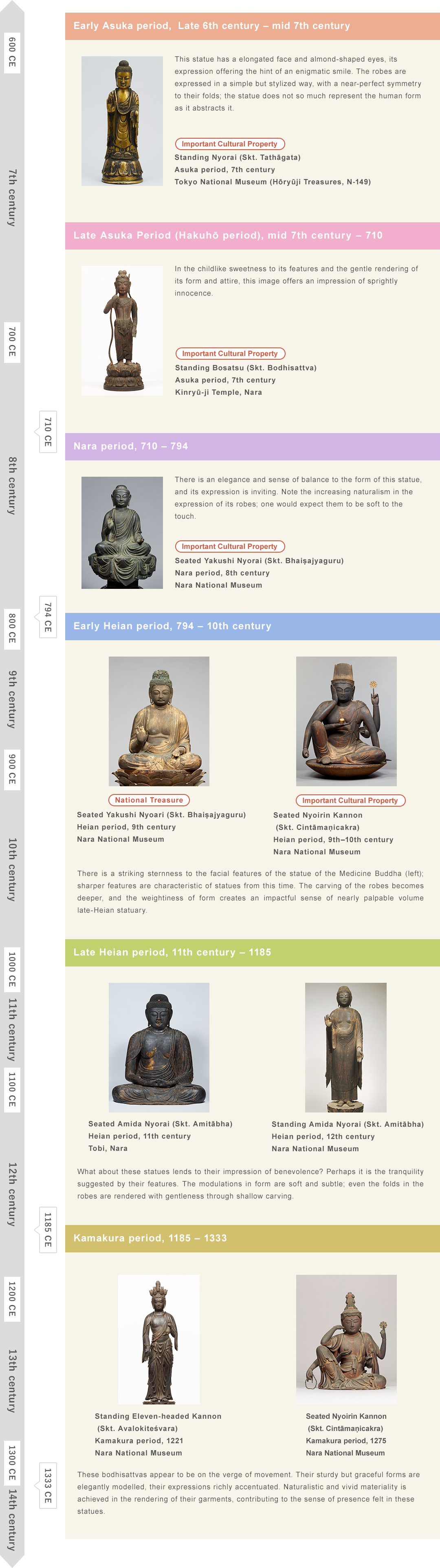

Stylistic Developments in Buddhist Statues